In many ways, Sunday’s eight-rider duel at Phillip Island came to encapsulate Maverick Viñales’ 2017. There was the initial promise, the expectation he would pose reigning champion Marc Marquez a real threat; he was doing just that before misfortune struck on lap 22, when Johann Zarco and Andrea Iannone put that kind of moves on him that would leave most dazed, confused and in need of the smelling salts; and then the late rally, the wiping out of Rossi’s advantage in four laps to finish alongside – but just behind – his decorated team-mate.

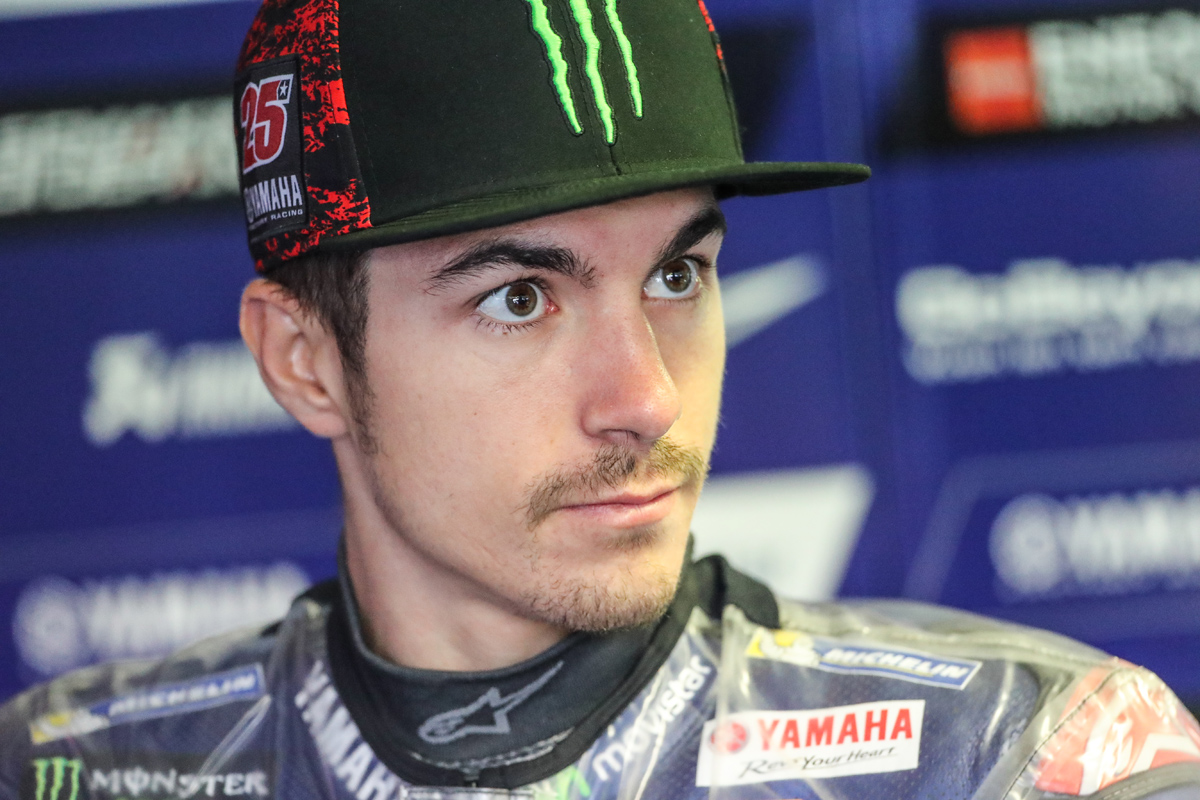

All in all, there was plenty to praise: a fine ride, his seventh podium of the year; an even better recovery from a position of peril; and a performance that, while not perfect, served as a timely reminder that a special talent resides behind that fixed, steely stare.

But ultimately, Viñales just came up short in a race he had designs on winning. There have been several of those afternoons (Mugello, Silverstone) through a frustrating and, at times, turbulent first season with Yamaha. With the title now out of sight – he sits 50 points back of Marquez, two races from home – a period of deep reckoning will no doubt follow the final outing in Valencia.

So how do we judge a year that started so bright, with convincing wins in Qatar, Argentina and France giving him the deserved title of early season favourite? It’s fair to assume Viñales will look upon it as a disaster, his blowing of a 26-point lead and a position of strength in two races a clear source of frustration as he made his way to the summer break.

But it would be unfair to label it thus? Considering his previous standing within Suzuki, slotting into the Movistar Yamaha ranks, alongside nine-time champion Rossi, in a team designed around the Italian was never going to be easy. And prevailing against Marquez – two years his senior and riding better than ever – all the more so. Mid-season did shine a light on Viñales’ lack of experience and fiery temperament however. Certain incidents underscored some current failings, and not just those apparent when on the bike – riding in the rain, or in the race’s opening laps chief among them.

Take his early-season gripe with Michelin for instance. Having failed to extract the most from the French rubber in Austin and Jerez, those close to Viñales revealed the 22-year old was convinced the French firm was conspiring against him. A means of firing himself up, of creating an ‘Us v Them’ situation perhaps, but with hindsight, this acted more as an ongoing frustration that gnawed away at focus.

Title rival Andrea Dovizioso noticed as much at Montmeló, Viñales’ ’17 nadir. “He wants to win, he’s really aggressive and when you find difficult conditions like we have at this track, you have a shock, and you can work in a bad way, you are too aggressive.” The same could be said of Texas and Assen, races he could – and probably should – have won but for an overly headstrong approach.

Then came the complications with set-up direction, with Rossi pushing in one way, Viñales another. The Spaniard wore a face of thunder from Assen through to Brno, the dawning of Yamaha’s decision to pursue his more experienced team-mate’s suggestions a sour pill to swallow in light of his own pre-season speed. Rossi’s occasional, pointed barb appeared to rile him further, a situation he will surely handle with greater assurance in ‘18. Yet it’s still worth noting Phillip Island was the first occasion Rossi had won out in an inter-team battle since June. Even when Viñales has appeared down and wounded, he had the beating of his elder.

And all blame cannot be apportioned his way. For one, Yamaha’s set-up direction appears confused. The M1 remains a machine incapable of dealing with the slightly inconsistent nature of Michelin’s tyre allocation, its ideal operating window a good deal narrower than that of its direct competitors – the Honda RC213V and Ducati’s GP17. Viñales hasn’t been the only one at a loss to explain the superiority of Johann Zarco’s year-old bike at certain rounds either. Rossi has struggled for the best part of a season, his criticism of the ’17 M1’s ongoing traction, electronics and wet weather performance mirroring that of his younger companion.

According to one prominent member of the Catalan press, there was an acknowledgement from within Viñales’ camp over the summer break that too much energy was being expended criticising set-up and Michelin – a sign of a willingness to take criticism on board, and iron out those faults. And while he hasn’t outscored Marquez in a race since early June bar that fortunate afternoon at Silverstone, Viñales’ battling responses to conditions that were far from ideal at the Sachsenring (bad qualifying) and Misano (wet race) were the sign of a rider operating extremely close to the very highest level (not to mention one possessing a supreme ability to deal with the most considerable of pressures).

Yes, all the pieces are yet to come together. But other than Marquez and Rossi, who else possessed a complete armoury at such a tender age? With the resources at their disposal, and a more settled tyre allocation for ’18, Yamaha is bound to work out a formula to extract consistency from its package sooner rather than later. A few tweaks to his own approach and ’18 could well be his year.

There have been strops and tantrums along the way but don’t expect this year’s veritable set of lessons to go unlearned. As ex-team boss Pablo Nieto once told me: “He always wants more, more and more. He’s never 100 percent happy.” Viñales has time on his side and those doubting his talent need only consider Suzuki’s struggles since his departure. Don’t imagine this streetwise kid that regularly took on and beat Marquez in his youth will be going away anytime soon.

Photos by CormacGP