It was easy to think about the past, present and future at Lommel two weeks ago.

Interviews with the likes of Gautier Paulin and Clement Desalle was a reminder of how MXGP and sport continues to move and is how these riders who are/were the reference of the category for the best part of ten years are trailing away. Then there was Tony Cairoli who seemed to labour across a track where he was formerly so quick and so powerful; the Sicilian admitted that his collection of 9th, 3rd and 5th results mean he had “thrown away the championship”. Tim Gajser (1st, 2nd and 1st), Romain Febvre, Jeremy Seewer and Jorge Prado showed (in a depleted MXGP field) how rampantly fast MXGP currently is. Watching riders like Tom Vialle, Isak Gifting, Thibault Benistant and Roan Van de Moosdijk barrel across the sand gave a pleasant window to some future names of the scene.

Off the track there were other reminders. The tough Belgian venue and the presence of people like Joel Smets, Marnicq Bervoets and Marc de Reuver guiding three of the moto winners was a throwback to how motocross likes to feed off its past heroes, knowledge and heritage. The locked Lommel gates and empty spectator banks were stark sign of the present-day times, and the eerie and disheartening silence that surrounded the racing as the bikes worked their way through the sand around the back end of the site was a forceful mark of where we stand in 2020. Positive Covid-19 tests, headlines of national lockdowns and restrictions (as governments decide that people cannot think for themselves and to-hell with constitutional freedom of movement) created worries about completing the season.

For the future of MXGP, questions started to bubble about 2021. Encouraging news about COVID-19 vaccines aside it would be very optimistic to assume Grand Prix racing will be back to normal in the space of just six months, which is not only very concerning for the promoters and circuits but for the sport as a whole. Publication of the calendar three days after the finale in Italy only erased a little of the uncertainty. Even if it does start in the surprising location of Oman (a high percentage of desert riders in attendance?) in late April will that be enough time? To me it seemed like an outline of dates, rather than a fixed list and the use of the accompanying word ‘provisional’ is highly appropriate.

2020 became a salvage operation, forced when the season had already started. 2021 could scratch new lines in the cement. There are other industries hard-hit by the need for public participation but the shape of MXGP as we’ve come to know it over the years could shift drastically in terms of less events, less track time, less international scope and potentially less investment as the show shrinks accordingly. The calendar is aiming for 20 events; how many will it actually manage?

Frustratingly, promoters are now back to working on a week-by-week, month-by-month basis on a very short-term strategy when it comes to national lockdowns and limitations. Who knows what ramifications the vaccine and legal process of disclaimers might have for professional sport and attendances in 2021?

Watching Ben Watson take his first Grand Prix win (and then do the double in Italy) was another symbol of that past, present and future. Watson joined the British duo of Shaun Simpson and Max Anstie to taste success on the hardest motocross track of them all and delivered the UK’s first MX2 win for four years. Watson was originally the next ‘wonderkid’ to follow three-times world championship runner-up Tommy Searle. He won his very first EMX250 European Championship appearance in 2014 after blazing a trail as a hyped junior together with brother Nathan. He now ages-out of MX2 and the fire and form he showed at Lommel to go 3rd, 2nd and 1st in the three meetings was overdue after losing most of 2016 and 2019 to injury problems. Watson added to Britain’s track record at Lommel, showed he is currently the brightest light of the country’s very few remaining GP racers (there were just seven Brits competing at Lommel, only one in EMX125) and filters nicely into Yamaha’s factory MXGP Grand Prix structure for 2021 where his large frame and technique could help towards a few surprises for what will be a learning campaign in the premier class.

The location of Watson’s achievement and his nationality also prompted thoughts of motocross’ place and time. Should Britain be concerned that there are no other promising youngsters emerging to follow his example and the slowly awakening potential of the talented Conrad Mewse? 2020 could be said to be an unreliable gauge for the health of the sport because of the logistical, economical and health complications involved to compete in Grand Prix and European Championship feeder/development series (Yamaha cancelled their YZ bLU cRU Cup for example) but, then again, perhaps those who have made it to paddocks in Latvia, Italy, Spain and Belgium are showing exactly the kind of resolve that is necessary to ‘make it’.

The quest for affordable racing has been a priority for years. But it feels like the screw has turned a few more notches. Britain has a strong and proud motocross past, a small but encouraging present but is the future a worry? Maybe not. “We have some really fast kids in the UK and these kids are investing quite a lot in academies and training schools,” says the UK’s best dirt bike tester, writer, former racer and two-stroke festival organiser Dave Willet. “The ACU don’t have an academy anymore but still help some kids…although getting some of them into Europe is proving tricky. Without always banging on about the price of the bikes and the lack of tracks it’s more about a lack of structure and people ‘passing the buck’ in my opinion.”

Watson himself believes the messy domestic situation in Britain doesn’t help. RHL Activities were quick to follow publication of the 2021 GP calendar with their own loose 15-date agenda for the ACU Adult and Junior championships. The MX Nationals will also be fighting for space and attention. Speaking with Ben for a recent RacerX interview he said “it is sad to see a series like the EMX125s – this is supposed to be the stepping stone to EMX250 – and by the third race in Lommel there was not one Brit in the class. I was watching the live timing and talking with Marnicq [Bervoets, Team Manager] saying that it was really strange there wasn’t a single Brit. He asked if there were any good young riders in the UK and I said I didn’t really know because there is no ‘real’ British championship for the kids. There are too many parallel series. There needs to be a single, British championship that carries some prestige. Money is a big part of racing of course but I think some of the fast guys need to try a couple of European rounds and measure themselves. If they are good enough on a bike and are showing what they can do in front of a GP paddock then the opportunities will come.”

Watson’s victory came at Lommel; one of less than half a dozen established tracks in the whole of Belgium. In MX2 and the EMX250 competitions combined there were only six native riders while Jago Geerts’ young shoulders carry a lot of expectation of a nation that were spoilt for choice for GP winners and personalities less than ten years ago.

Back to the interview with Paulin, which was another that appeared on the RacerX website after ‘Lommel 2’. It was comforting to hear him talk of how the French Federation’s proactivity has been a welcome rod of iron for the sport. The French are still the most powerful nation in motocross outside the US and have yet more athletes flowing through the pyramid thanks to shrewd talent identification, sensible support and preservation of tracks and places where kids can ride and learn.

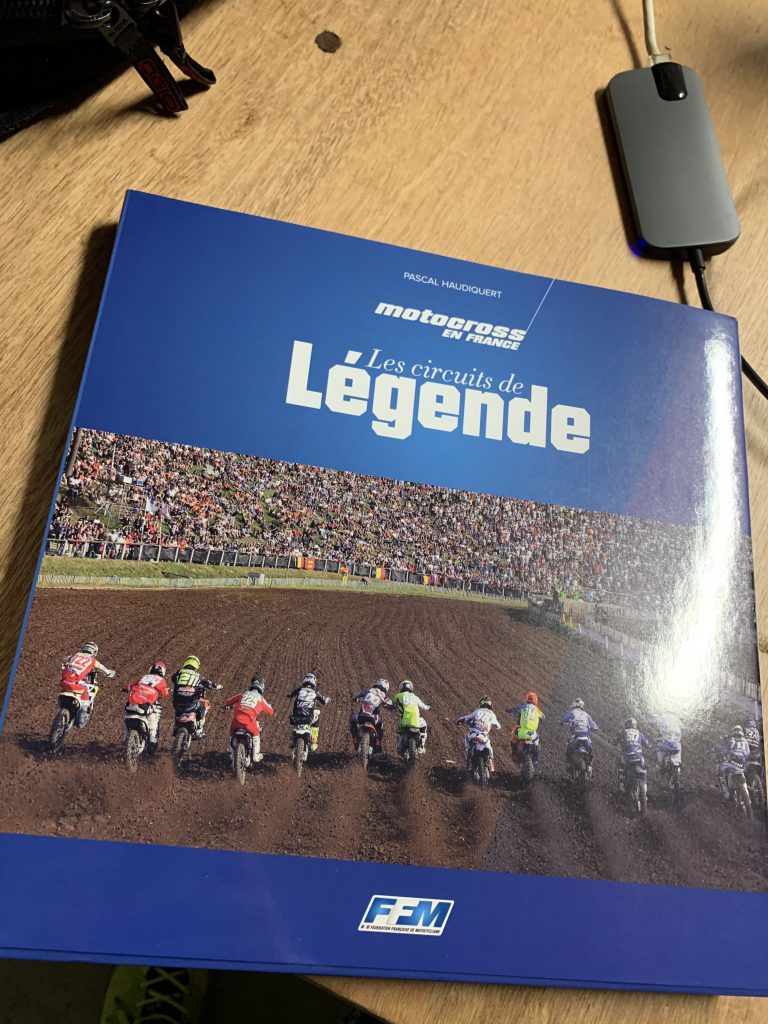

Renowned French journalist Pascal Haudiquert presented me with a quite wonderful picture/historical book he took great effort in producing in conjunction with the Federation, describing and commemorating 48 tracks that have hosted a French Grand Prix. He believes around 38 still remain. Does anybody else celebrate the sport in this way? They might soon have to if they want the benefits of community, revenue, excitement and a following that it gives. It’s not all doom-and-gloom however. Taking the current European classes as an indicator then it’s clear that countries such as the Nordics and Eastern Europe are producing kids that are hoping to make the grade. As in any generational shift when the big names and the big memories are eased to one side, there is small void where a lot more stories are waiting to be written by names that could become heroes as well.

By Adam Wheeler @ontrackoffroad

Photos by Ray Archer @rayarcherphoto